SOIL MATTERS

In the final embers of a life well lived, Charles Darwin became fascinated by worms. Late at night, at at the end of his garden, neighbours would see him shining lights, playing music, shouting into holes, and feeding cabbage to worms. He was quite sure they possessed an intelligence greater than we understood.

Across 30-years, he had watched on in wonder as these same worms turned the field behind his house – one with flints the size of a child’s head – into smooth, fertile soil. In his final body of work – ‘the formation of vegetable mould through the action of worms’ – he payed homage to this great act of hope.

While I am not playing the banjo at the end of my garden, like Charles I have become interested in worms, and more precisely in saving our soil.

Currently 1/3 of the earth’s soil has lost the qualities required to support life. Reversing this trend, while still feeding a growing population, is a critical and complex issue. An issue on a scale that I struggle to comprehend, and will leave to minds more magnificent than mine.

Where I feel that I can make a difference is on the ground itself. In the 20-acre field that my Dad has given me to farm, to give back to the worms. And in the human stories. Tangible, intimate, and relatable. Stories of hopefulness which can create a wave of fertility.

This is why I headed out to meet a few faces who know a lot more than me about the importance of soil, and of what we put in our bodies.

Local farmers tackling a global crisis. One carrot at a time.

Close Farm, Highgrove

“I sell real food. It is a badge that I wear with pride. Our gut is our second brain, and yet it isn’t treated like that. More than 80% of human illness is from diet, because food is not food anymore. We simply don’t know where the majority of it comes from. I have had a few lives before this one, including time as a tank commander back home in the Netherlands, but my roots were always in the land. I travelled the world, working the seasons. I learnt to sheer sheep in Tasmania, which is a craft I have passed onto my son. This patch has been home now for 23-years. I used to farm over more acres, with a team, but now I find it easier to work alone. I calculate what I can achieve in six 12-hour days, and work back from that.”

My carrots recently won an award for having the highest percentage of nutrients, up against 20 other farms. That is what I do it for it. My job satisfaction comes from the act of nourishing others. I focus on feeding the soil, not the plants. Healthy soil means healthy food. The nutrients start disappearing just 30-minutes after harvest, which is why a stockless system is the only way to deliver food that is actually good for the gut. Real food is always local food.”

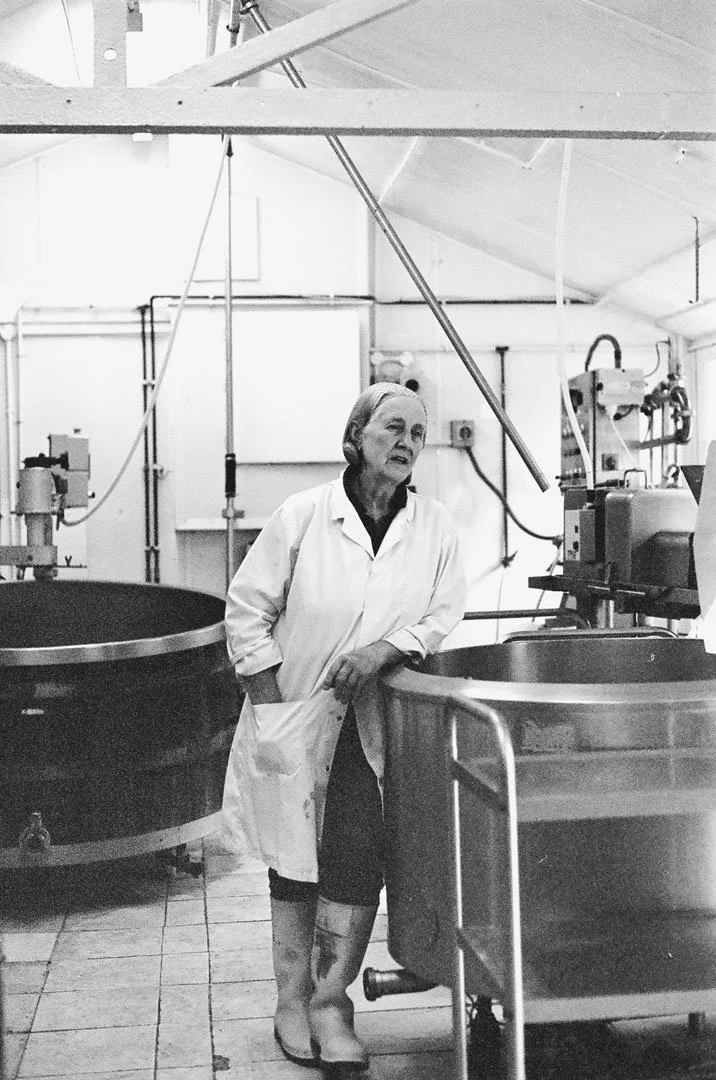

Woefuldane, Minchinhampton

“All our cows have a name. They are a part of the family. We know them personally, and intimately. When Violet died recently, aged 20, we were heartbroken. Thankfully, her grandson, who is aged five now, carries on where she left off. It was shop keeping which I knew as a child. My parents ran one. At school I was encouraged towards a career in teaching. But my heart was set on farming. So, I took myself off to agricultural college, met my husband, and the path was set.”

"We had no land so started with sheep and cows. Our close relationship with these first small flocks, still informs how we farm today. They are out for 11-months of the year, and are in only at night. We have 45 milkers, 25 newborn calves, and 13 heifers. These youngsters have the run of Minchinhampton Common, to play on and graze over. We milk them once-a-day, producing 3,500 litres per week, which we bottle by hand."

"This milk, along with our cheeses, is sold in our shop – which our sons runs – and then only locally beyond that. The secret to the quality of our produce is our soil. We have been working to save it ever since we got here, and after 20-years it is just starting to come into its own. Our children’s interests lie elsewhere, so we don’t know what will happen to the farm after we finish. When that time comes, all that really counts is that our soil and our flock continue to be well loved.”

Forbidden Fruit and Veg, Badminton

“I was working an office job in Bristol, looking out the window, and wondering ‘what else?’ I headed for Europe, and volunteered on organic farms in Spain, and Portugal, before returning to work on a plot in South London. I feel quite sure that small scale food growing is an answer to a large scale problem. With more people growing small, and delivering local – like we do here with our boxes – the price for good food can be brought down to mass affordability. Our polytunnels help with the shoulder seasons, but ultimately people are going to have to get used to eating seasonally. Year-round worldwide produce cannot sustain. The volunteers here – the ‘Woofers’ – like me before, have caught the bug for seasonal and sustainable growing. With more education we can get more growers, and eaters, on the same diet. From there, it is a domino effect. At the centre of it all is community. Sharing local, eating local, and sustaining local.”

Knowle Farm, Bowerchalke

“I guess I want people to understand that it’s really hard to grow a crop or keep an animal alive. In a sterile supermarket you don’t get a sense of that. You don’t see us out in the fields in the depths of winter, when the best that can happen is that nothing dies. Often with animals, people think it is a bit of a fairytale, but it isn’t. The foxes and badgers will kill a few, a mother might reject its lamb, or the crows can come in for one that has fallen over. It is our job to protect them. It is our job also to protect the environment. As farmers we have a big responsibility – and a great opportunity – to restore and regenerate our lands. My parents have always been good at getting people onto the farm, and we are trying to continue that. We had 500 visitors for our lambing day, all going away with a greater appreciation for farming. Hard work and success don’t really correlate in this world. You can put all the hours in that you like, and still a sheep will get its head stuck in a fence, or you will miss something. It is hard not to take that personally. I find it difficult also to take holiday. Even in the pub I suddenly think, ‘damn, I haven’t done this or that for the sheep.’ The job is never done, but nor is it ever dull. I tried other jobs, but I got bored and distracted. People often think of farming as a lonely pursuit, but we are a part of a brilliant community. There is a sense of camaraderie that runs up and down the valley. And also through time, to members of my family – on both sides – who have been farming for hundreds of years. It is all that I have known, and all that I ever wanted to do.”

Weight in Mind, Shipton Moyne

“I still remember my first job in a kitchen. It was my Dad’s cousin’s restaurant and I was tasked with peeling carrots for £1 an hour. It was the start of my love affair with food. By 17 I was a sous chef, and when I headed on to University, I was able to fund it by catering. What I really care about is the interrelationship between nutrition and health. It is clear that our health span does not match our life span, and a big part of this is the neglect of our gut. Whether it is for our skin, happiness, hormones, or physical wellbeing, our gut holds the key. It is the engine room of human health. Cancer is still being treated by Chemotherapy, a measure introduced in the 1860s. Yet before this is required, we can prevent the vast majority of these illnesses through rethinking our nutrition. Through learning from the wisdom of historical ways. Along with many others, I am hoping to bring the rhythms of human life closer to that of the natural world. Human nature and nature are one and the same. A single system which has been disconnected. I can sense that the tide is turning though. The world is waking up, and it is an extremely exciting dawn for nutritional health.”