MILLIMETRES

2 MOUNTAINS

In 2017 Ed Jackson, the professional rugby player, dived into the shallow end of a swimming pool and brought to an end his former life. I watched on with admiration and amazement at how he faced his new reality. A reality which was immediate, unwelcome but not final.

Lying quadriplegic in hospital he could wiggle his big toe. Despite his career and his identity – one he had a spent a lifetime creating – being stripped from him, he called himself ‘lucky.’ Lucky that his big toe could move, just a few millimetres, and that this movement gave him hope.

At this same time I was struggling with depression. I felt lost beneath a shiny exterior. I sought but did not yet possess the courage to write a new narrative.

In witnessing and interviewing Ed, not long after the accident, I saw a man walking towards his future, not running from it. The canvas was not of his choosing, but he still held the pen.

This seemingly innate desire to shape the narrative was infectious. His recovery – from a hospital bed to the top of a Nepalese mountain – was an invitation to others. To anyone who faced a physical injury or a mental illness. An invitation to see it not as a full stop, but rather a comma. The script that followed was yours to write.

This through this mindset, and the cathartic power of the natural world, Ed and his wife Lois created the charity Millimetres 2 Mountains.

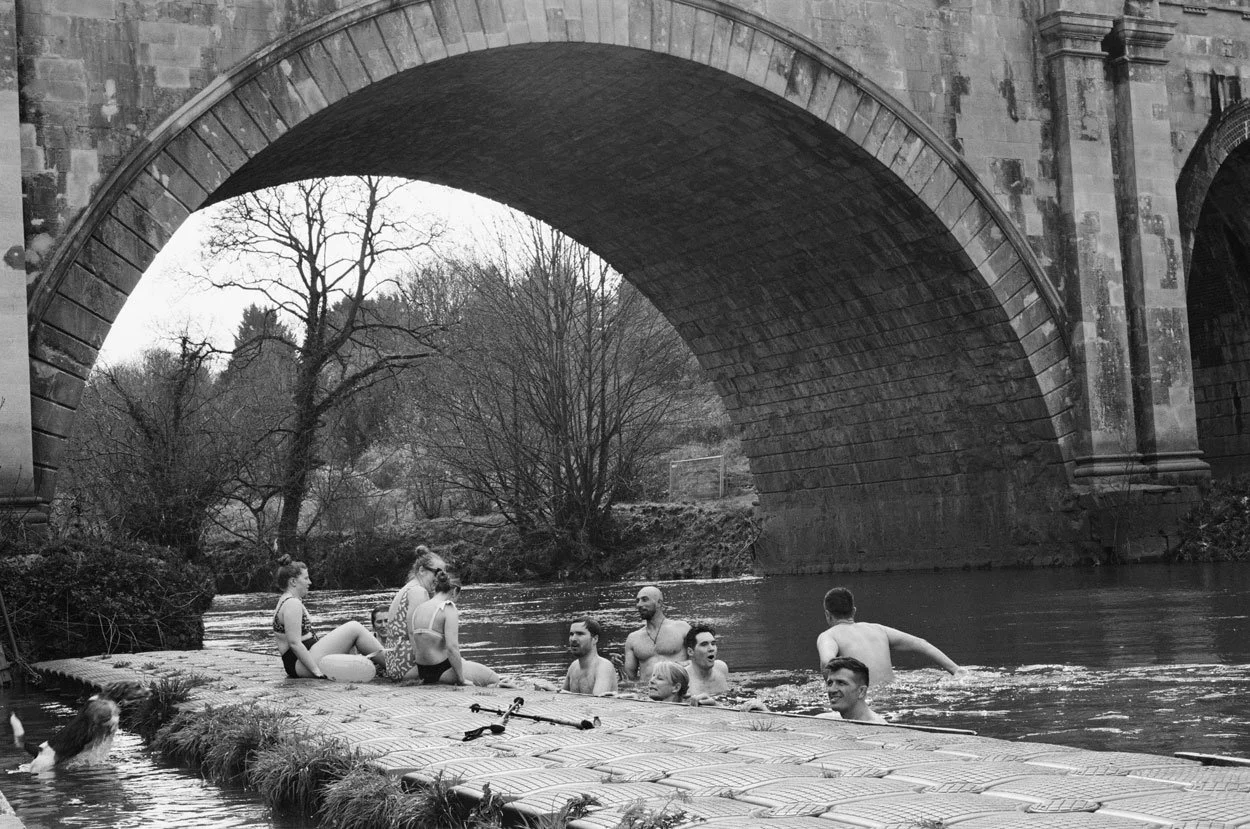

I spent a weekend under canvas, offline, and in community, with this brilliant charity. It gave me a snapshot of the charities simple philosophy of pairing the natural world with a sense of belonging, to rewrite narratives.

I had the deeply inspiring and emboldening task of capturing five of these narratives.

“I remember being tackled and thinking ‘ow no, this isn’t good.’ I had broken my clavicle, dislocated my sternum, and ruptured the artery which supplies blood to the brain. As I lost consciousness, one of the parents – an off-duty medic – saved my life, using a kitchen knife to open my chest and allow air to flow.

My Dad wanted to jump out of the hospital window when they told my parents that there was no response in my pupil and the advice was to turn off the machines. They were distraught. But my Mum refused. She knew that I could pull through. The only option was a craniotomy. And a month later, at the third and final attempt, I woke up.

I think I rushed going back to school. I was 16 years old, impatient, and in denial. I spent the rest of that school year – more than seven months – with half a skull, and just a hat covering the gap. I couldn’t walk anywhere alone, for risk of falling. So, I had nurses 24/7. I needed to relearn everything, all my physical movement, my social skills, and cognitive processes.

For a long time, and for the first time, I was depressed. Really sad, and in a dark place.

Many of my best friends, they left me. They were too young and too ill equipped to deal with it. But in their place, new more meaningful friendships emerged – people who I wouldn’t really have crossed paths with before.

Sport, friendship, and family, these things healed me. As soon as I was allowed, once I had a metal skull, I was running. Running with the new nickname of ‘Titanium Tom!’

I feel like I have experienced every human emotion in the past seven years, and I received the rarest of gifts. The gift of understanding how precarious life is. When I got injured, that was the last thing I expected to happen that day. You learn in a moment, that you have no idea what tomorrow will bring.

When I was first told about M2M, I was sceptical. Too many times I have been promised the world by charities, and it hasn’t materialised. But right from the off, I was in physio, meeting cool people, being supported, and doing amazing things. Last week I climbed Snowden, this week the retreat, and in November I am heading to Nepal.

Often in social settings I try to mask my injuries. The twitch, or the spasms. But being here, with this incredible group of people, I can be completely myself. With a brain injury it is difficult to know what is ‘me before’, ‘me maturing’, or ‘me changed.’

One thing is for sure, I certainly wouldn’t have been doing breathwork before the injury. I did think, as I lay there, ‘imagine if my brother saw me now!’ But it works. And in life you have to do what works for you.”

“The diagnosis came as a bit of a relief. Despite the difficult reality of being told you have a terminal illness; I finally had some context for the past six years of my life. It took more than 10 visits to intensive care – all before my 21st birthday – for the answer I needed.

The warning signs were there from the very first head injury, when I was just 15. What should have been relatively routine instead required hospitalisation. I knew instinctively – despite being told otherwise – that there was more to it. After the second head injury, I spent a year in hospital, learning to talk, eat, move, and even remember. Still nothing was detected, and in truth I did not mind. All my focus was on my boat.

I can still recall the day that I fell in love with the water. With rowing, with kayaking, and with the thrill of competition. Despite being five years younger than my brother, I raced him, and I beat him. I got out the water and said to my parents, ‘I want to go to the Olympics.’ I wasn’t particularly serious about school, but I was about racing. It gave me an avenue for my energy.

In the midst of that second recovery, it also gave me a purpose. As soon as I got home, I said to my Mum ‘I want to get in my boat.’ Although I could not walk, I could row. And 18-months later I was on the start line of the Junior World Championships.

At university, as I would head out to train at 4:30am my flat mates were stumbling home. I missed out on that part of being a student, but I didn’t mind. I loved what I was doing, and the people I was doing it with. After I got selected for Team GB, I remember thinking ‘f$%k, I am actually doing this!’ After the injury I was told that I would never get back, and yet there I was. Fulfilling my childhood dream.

When it happened again – for a third time – it was incredibly difficult. This time I knew what lay ahead, and that awareness was scary. A canoeing accident left me fighting for my life, causing me severe internal and external injuries, as well as complex neurological issues. My family were told that I had a 2% chance of survival, and it was five months before I have any conscious memory. I went off the waterfall in the Autumn and I woke up in Spring.

The first two recoveries I did not struggle mentally. But this third time, hidden behind the humour, was an avalanche. Last winter, after a series of upheavals in my personal life, the scales were tipped, and I broke. I experienced this huge sense of loss. An overwhelming sense. It was once again my boat which saved me. As soon as I was strapped in – able to hold just a single oar – my face lit up.

I had just begun to get my life back when I was sent – once again – towards rock bottom. This time it was a spinal stroke, and this time – six years on – MELAS was finally identified. It is an extremely rare mitochondrial condition – which can occur at any age and often out of nowhere – affecting my cells’ ability to heal, putting my organs at risk, and creating a domino effect of ill-health. MELAS has only 30-years of research behind it, meaning the doctors are at a bit of a loss with me. But in the face of this darkness, I am trying to find those shards of light.

One particularly bright light is the many people who support me – the ‘Carmichael Can Cult’ as they like to be known. They have shown that they are here for everything. For all of me. It is a depth of love and care that I have not known before. In this safety I have started to remove my mask of positivity. To let people in.

Before I was ‘Georgia the rower,’ or ‘Georgia the athlete.’ But who could be found beyond this identity? I like to think of this discovery – of a whole new part of me – as a rainbow. In the rain is the grieving process – which I never did properly before – for my former life. And in the sunshine is this evolution.

While I am physically stuck in bed – for now at least – I have in fact found a sense of freedom. I understand now that I am not trapped by my mind. It is a choice. And in this choice – in this new-found vulnerability – there is hope.

I can use my story to help others. So, if further down the road someone is in my situation, they will know that there is a route through. It is what Ed has done so brilliantly with M2M. Encouraging people to flip the focus. To notice all the things that they can do, and that they already have. In what is going to be a long road ahead, this mindset is vital for me. It is the same mindset which will – I am sure of it - take me back to my boat, to the start line, and eventually to the Paralympics.

I know that the rain can become a rainbow. I have done it before, so why can’t I do it again?”

“For as long as I can remember, rugby was my identity. Those formative years were the best of my life. The training, the fitness, the physicality, the camaraderie. I just loved it. I played for England juniors, and then semi-professionally in the U.S. and back home in Bristol, right up until the accident.

I was sat on the back of my friend’s car, with the boot open and my leg hanging down. The car behind lurched forward, and that was it. In a moment, my identity and my former life – playing rugby and working the doors – was gone.

Remarkably not a single bone was broken, and it meant I was dismissed with severe swelling. It was not until the sixth weekly check-up that they noticed something was wrong. I had Compartment Syndrome, and the next day they removed a cavity that ran the length of my leg. What followed was four operations, and three bouts of sepsis, the final of which nearly took my life.

My biggest challenge though was the shadow it cast. I had my family in my corner, but I lost a lot of friends. I couldn’t show up like I used to, and they faded away. I could not exercise, and I developed massive body dysmorphia. I really couldn’t stand myself.

There were many dark days. You find yourself searching for the slightest gap in the clouds. Something to hold onto. One such gap was the day that I got a video call from Lois and Ed to say that I had been accepted. It gave me hope. I knew then, that for three years, I was a part of something. Connected with like-minded people. People who had gone through far worse than me, and still they found a way. It is inspiring. If they can do it, then so can I.

My old fitness coach in Bristol believes in me. He told me that we could get back to where I was before, and we have set to work. The gym was always my ‘get out.’ After a bad night on the doors, or a disappointment on the pitch, I could process it through exercise. Having that back in my life has been another gap in the clouds. Adding to this sense that things are beginning to change.

Through it all, the one thing I was never going to do was let my son down. He is nine years old, and already this accident has cost him too much. I missed his first day at school and his sports day. We haven’t kicked a football or gone on holiday together. But we will do these things. We will go to Legoland, as I promised him and as he always talks about.

I hope that he understands. I think he does. He often says to me, ‘when you are better, Daddy.’ That thought keeps me going.”

“It came on suddenly. It was Christmas Eve, so I was surrounded by my family. My dad is a doctor, mum a nurse, and brother a neuro-scientist, so we are well versed in medicine. The consensus was that it was likely spasms. However, after seeing my foot drop, my dad became concerned. It is a sign that something is wrong with your Central Nervous System.

Within 24-hours I had lost the use of my left side, bladder, and bowels. I think if I knew then what lay ahead, I would have been scared. But as a sportswear designer, with an keen interest in the body and no knowledge of what was to come, I was fascinated. I was lifting my arm and just watching it fall.

It is a neurological condition called Transverse Myelitis. Effectively your immune system attacking the body. It is extremely rare, and with little research. They still don’t understand how you contract it. Emma, who is also a part of M2M, is the first person I have met who has it.

It is eight years now, and while it has steadily improved, it hasn’t been linear. Each year, there is a complication, and each month, with my hormone cycle, or any other stress on my body, I am set back. This can lead to months of fatigue. It makes doing my work, and building my life, extremely difficult.

The loss of independence was incredibly frustrating. Suddenly, aged 30, my parents were my carers. At first your friends are with you, but as time passes, realising this is a long road, they drop away. The same was true of my relationship at the time. What this does do however is create space for new, stronger connections.

My Mum would create a bed in the garden for me. It was the only place I felt safe. I have learnt to tune into nature’s frequency, and into my body. Reading the Tibetan Book of Living and Dying, it helped me accept it. For so long I was fighting. Trying to conform, to keep up, to get back to normal.

In confronting my own mortality – and there have been many touch and go moments – I also witnessed the death of my identity, and my former life. There is great freedom in this surrender. Trusting where your life is headed, and not struggling against it. I think it has made me a nicer and better person.

I have major imposter syndrome about being here. I feel that others are more deserving. But through this experience, I am realising quite how badly I have needed this community. To support and expand me. It came, shortly after a complicated operation, when I had lost a little of my spark for life. I love the emphasis on creating new narratives, which is what I am all about. Realising that there are so many other narratives for me.”

“While I work out what I want to do next, I am working in a library. As I put the books back on the shelves, I am reminded of all the stories I read as a child. I loved reading. Disappearing into another world. This is the start of a new chapter for me. Away from home, from my family, and my past. Building a life with my girlfriend.

I fancied her for two years at university before she finally spoke to me! I am learning now what it means to be in a healthy and happy relationship. Sometimes we will be doing a lovely activity together, and I will suddenly feel guilty or sad, as I find myself thinking back. As a child I was happy, despite things being messed up around me. But as an adult, I understood that these things were not okay. It was hard after that, to hold onto the lightness, or to be the same again.

It comes in waves. There will be periods where I think I am through it, and then three months of just being in the pits. It wasn’t until university that I received the diagnosis. Before that, I didn’t know what it was. I would just feel incredibly low. Like whatever I was doing was pointless. A total absence of motivation. This meant I made less effort and invested less in relationships. It fed itself. Becoming a cycle.

If I had to pick a colour, I would say red. There was a lot of anger. Anger towards my parents. Anger at life. I had to stop playing football because I kept getting sent off. I just didn’t care, and it became this place where I allowed myself to lash out.

I hardly left my room, for the whole first year. But gradually I started to emerge. To make some friends. I started to sense that maybe, just maybe, there were some people that I could be myself with. If you ask my girlfriend, she’ll tell you that I can be pretty wacky, but it takes a long time for me to feel safe enough to be like that. These same people are still my best friends today. I know that they have my back.

Both my girlfriend and I have joined a netball team. Sport gives me a voice. When I am on the pitch, and in a game, I can direct and shout. This competitive edge takes over. As soon as the whistle goes though, I will be back at the back of the group, quiet and calm.

She encouraged me to put myself forward. I struggle with saying ‘why.’ But I think the process of writing rather than speaking helped me. I have been stung by people’s reactions in the past. Some friends couldn’t handle it and stopped coming round. I was emotional as I wrote the application. Stopping, and returning. But it felt good to do it. To share. That is why I went back to finish it. When Lois rang, I was sure it would be ‘thanks but no thanks.’ In that moment I thought ‘maybe someone heard.’”